Fresh From the frank Stage

Standout talks from the most recent 2023 gathering, featuring bold voices, urgent truths and unforgettable moments.

Amahra Spence

Liberation Rehearsal Notes from a Time Traveler

Shanelle Matthews

Narrative Power Today for an Abolitionist Future

Nima Shirazi

Irresistible Forces, Immovable Objects

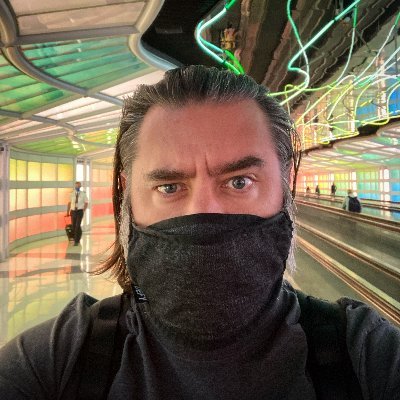

The Speaker

Brian Boyer Freelance Writer

Brian Boyer is a product-and-data strategist with 25+ years of experience spanning software development, data journalism and newsroom product leadership. He’s helped launch analytics programs, CMS migrations and audience-first digital products for nonprofits and media organizations.

Go To BioWatch Next

Our Impact is Empathy

Behavioral ScienceEducationEmotional IntelligenceFamilyJournalismStorytelling

Transcript

systems are perfectly designed for the results they attain. Think about that. I’m going to say a bunch of stuff. I might forget to say that, but it’s important for my talk, too. All right. I’m rolling. I’m Brian. I used to be an unhappy programmer. That’s not me, but… But I was sad like that. I was working in Chicago doing the things that software people do in Chicago, which is make software for bankers and for marketing teams at banks and building productivity tools for lawyers. And I loved the craft of making software. I love making things. But the work at the end of the day was just soul-sucking shit. I mean, my job was to make rich people richer every day. And so I was considering a degree in law. I was considering a degree in public policy. I wanted to get out because I wanted to use my skills to make the world a better place. And then it randomly happened upon a fortuitous blog post on Boing Boing that Northwestern University was giving scholarships to software developers to study journalism. Now, I was the cartoonist for my high school newspaper, but I had never considered journalism as a career, so I Googled journalism. I didn’t make that up. I literally did that. And I read about its mission and I read about its system of values and I read the journalist’s creed. And I realized it’s what I wanted to do because law and policy were top-down solutions to these problems that I wanted to solve. And journalism was from the bottom up. It was about informing people so they could better self-govern. And that really struck a nerve with me. So I dropped everything and went back to school. And it’s been a hell of a ride ever since. I interned with ProPublica and then got a full-time job at Chicago Tribune where I founded a team of hackers and data journalists. And today I’m the visuals editor at NPR in Washington, D.C. Scott, who you saw earlier, is my boss. Now it is a first slide. Whoa, okay. Where’s my people? I think I skipped a slide. All right, keep rolling. It’s a weird and awesome kind of person who decides to work on a visuals team at National Public Radio. We’re a team of 15 misfits. Hackers, we’re engineers or photographers and producers who make graphics, photography. We do data analysis. We do reporting. And we create all kinds of fancy, shiny shit for the web. Now the history of visual journalism at NPR is relatively brief. So there hasn’t been a lot of structure around our role. And a couple years ago we got to asking ourselves, what is the role of photography at a radio organization? What kinds of work should we be doing? And since we didn’t have a newspaper to support, we could ask ourselves things like, what is a web-native chart? Not just a paper chart. What is web-native photography? What’s that mean? What can it do? And in journalism and in the greater sort of do-gooder world, a lot of time is spent talking about impact and impact measurement. There’s certain conversations you have at work. And sometimes it’s quite tangible, right? When I was working at ProPublica, we saw impact at the halls of the Congress building, right? At Chicago Tribune, impact was throwing a governor into jail, which we do a lot in the state of Illinois. But at NPR, impact is a little weirder. We don’t do a lot of accountability journalism. Not that we don’t do it. We don’t just don’t do a ton of it. And honestly, it kind of bummed me out. Until I realized that the power of radio was hearing someone’s voice, hearing them tell their story, was really different than reading it. And so if that’s the power of radio, what’s the power of a graphic or a photograph? And it’s not that different. I mean, a picture can instantly make you give a shit, right? Like we saw in Molly’s talk yesterday, images have remarkable qualities. And a picture that we have come to think of it is like a little empathy machine, right? And so that kind of became our mission at NPR visuals, that our impact is empathy. That’s what we’re trying to create in the world, that our mission is to make people care. Now, that’s awesome to have a mission. I’m certain some of y’all have mission statements and things. But it’s not enough to merely have a mission, right? You’ve got to do the work, right? And then, but how do you know after you’ve done the work if your work worked, right? How do you know if you’re succeeding at the mission you’ve set out for yourself? And the question, of course, is how do you measure success? Well, I tell you what, the measures we have for success are fucking terrible. At best, page views, which are quite easy to measure, Google tells us those. That’s a system that is creating the results to attain, that we said earlier. They measure the success of your headlines or maybe how good you are at pandering. And then there’s awards, that’s our Emmy. But awards only really measure if you’ve impressed your peers. And I love my peers, but you’re not my audience, right? So, a year ago, we decided if all that stuff is bullshit, then what should we measure? And we said if our impact is empathy, then shouldn’t we be trying to measure that? But how can we measure if something we made made people care? Well, unfortunately, we cannot put our audience into an MRI machine and just measure them while they’re reading a story. So we needed to find other measurements. We needed to think of measurements that could act as proxies for giving a shit. And there were some things we already got from our analytics tools, like you could tell how long someone spent reading a story. But we also started building new measurements. We built a button on our stories that asks you things like, did this story make you care? Yes or no? People totally click that button. Another metric we made up was taking the number of shares a story got on Facebook and dividing it by the number of pages. See, we’ve pages into the denominator for math nerds here. So what percentage of the people who read this piece were then moved to tell their friends about it? I think that’s an okay measure of giving a shit. But my favorite measure is something we’re calling an engaged completion rate. I clicked the wrong button. All right, so a bunch of our work has this little begin button you’ll see here. Some people click it, so they arrive at this page. Some people click that button, some people don’t. It’s common across the web. A lot of people show up at a web page and leave. Those pages shouldn’t count. Throw them out. To measure an engaged completion rate, we count the number of folks who did click, and then from that number, how many of those people actually finished reading the story? So it’s a measure of once we hooked you, did we hang on to you. So we got a lot of numbers. But now what? It’s good to know things, but if they don’t change your actions, what’s the point? And the way I see it, there are kind of two big things you can do with your metrics, or metrics in general. The first is to optimize for success. So we have restructured our team so that we are better suited to make things that perform by measurements that we like. That’s maybe obvious. The second, though, is much less obvious, and I think more important, is that you need to be really good at celebrating success with your own team and with your organization. So for example, this is a story about the Civil War in Yemen. This is a long story. It’s difficult. It’s foreign. It’s fucking sad. And it did about 60,000 page views. That is not a huge number for us. Some of our pieces will rack up hundreds of thousands or millions. And everybody wants to see their story reach a lot of people. That’s part of our goal as journalists. We like to tell stories from reach people, and that’s okay. But when you do a story like this, when you’re not going to get a lot of page views. But of the 60,000 people who visited this page, 50,000 of them click begin. I’ll take that. That’s a decent version. And 70% of those people actually finished the story. Like 70% of those people spent like 10 minutes with us thinking about the Civil War in Yemen. Let’s eat your broccoli shit, right? And so, yeah, that kind of completion rate is incredible. So I’m going to take a diversion here for a second. This is a door, not far from my desk at National Public Radio headquarters in Washington, D.C. If there are any design geeks in the house, what is it called? It’s called the Norman door named after Mr. Donald Norman, the fellow who more or less invented the study of usability. His book, The Design of Everday Things, is a delightful book. And it’s full of, I love it because it’s full of forgiveness. Like this remote control that’s hard to use, it’s not my fault. Your terrible time tracking software, it’s not your fault, right? This stupid fucking door that gives you no clue whether you should push or pull is not your fault. It’s badly designed. And yet we have them. We just moved into this building like a year and a half ago. Our building makes very smart people feel very stupid every goddamn day. And you know what else makes smart people feel stupid? Our daily analytics email. This is a list of stories that got lots of pages yesterday. Sometimes it’s breaking news, sometimes it’s a no-k piece of journalism, but it’s just as likely to be a list of stories about celebrities and back pay. And it’s almost never a list of impactful, important journalism worth celebrating. Now the doors and the analytics here, at least I see them as structures in our work environment. And they’re both demoralizing. We chose to create these things and we put them where we work and they influence our behavior. And whether it’s not important, they are the enemy of good work. Oh man, I’m out of schedule. I can ramble a little. So how do we fight this enemy? Well, we’re currently building a little project called the Care Bot. We hope it will be a structure in our environment that will celebrate good work and it’ll be a structure that reinforces our mission. The idea is when we publish a story, Care Bot will discover it automatically and deliver messages in our team’s Slack channel, which is the hip thing to do in our day, Slack Bots. And it will tell us, ideally, hopefully by measurements we’re inventing right now, and we’re playing with. It will tell us if people cared about our work. And instead of sort of one-mine-e-mail, we’re trying out a little conversational user interface, which is kind of fun. And our project is open source. You’re all welcome to play along. We’re blogging about it. We’re writing about our ideas. And you’re free to try this thing out in your organization, which is cool. Sounds fun. Free tools. Everyone wants one free tool. But the thing is that we’re building something that works for our mission. And what we’re making is not going to solve all of your problems. This is something you all have to figure out for yourselves. And to do that, you’ve got to know your mission. You’ve got to measure things that matter, not just the easy shit like Google Analytics gives you. And you’ve got to create ways to celebrate success among your team and your organization. And then maybe that’s a robot, or maybe that’s just a healthy shout-out at your team’s morning meeting. You’ve got to create structures that reinforce what you believe. Thanks.

Watch Next